"Pfft! A prince, a prince...Now where am I supposed to find one of those?"

Ahh, that age-old question....

Emile Bravo is an award-winning French comic writer and illustrator whose work for older children and adults I have been drawn to for its originality and emotional depth. His Seven Squat Bears series (The Hunger of the Seven Squat Bears, Goldilocks and the Seven Squat Bears, Beauty and the Squat Bears) is his first foray into writing for younger children, and he handles the transition with panache. The Squat Bears were an instant hit in France, and it's not hard to see why. They're all clever fairy-tale mash-ups which are full of personality, funny as heck, and just right for an elementary-school audience. Beauty and the Squat Bears is my personal favourite, with its zany plot and derriere-kicking fairy godmother.

So what do I like so much about these books? First of all, I love the drawings...especially the bears. They're the straight men in these stories and their expressions are priceless. Especially when they're being grouchy and cynical.

Bravo's illustration style has been described as "clean, expressive and ironic." I think his style, which is actually quite detailed although it manages to look fresh and uncluttered, is perfect for this age group. I like the rich, saturated colours he uses. I also like how he hasn't made the bears "cute". They really are squat, rectangular almost, and it gives them a very business-like appearance. Especially when they're stalking through magic forests looking for princes to solve their princess problems.

The dialogue is snappy:

"'Ohhh! Pleeeease, let me stay with you. I'll do whatever you want...'

'Even chores?'

'Huh? I don't think so! After all, I am a princess...'

'So, what can a princess do?'

"Huh? Well, marry a prince, duh!'"

And a little later on:

"'Alas! A sorcerer put a curse on me that turned me into a bird for seven years...'

'Seven years! No way! That'll never do! I need a prince right here, right now. It's to get rid of a princess!'

'A PRINCESS?! HOLD ON, WAIT! WE CAN WORK THIS OUT!'"

I've heard that there is a fourth Squat Bear book coming out in french this year (Le Sept Ours Nains et Compagnie). Hopefully the translation will be with us soon!

Friday, December 23, 2011

Monday, December 5, 2011

Life: An Exploded Diagram by Mal Peet

"I'm hoping that Life is the book that proves to be Peet's breakout book. For starters, it's got a penis on the cover. Wait, did you think that was a missile? So did I. Then I brought my ARC down to the cafeteria while I was reading. Teenagers are very fast to clue one in about suggestive covers, it turns out."

(Karen Silverman, Heavy Medal blog, School Library Journal website)

Mal Peet can't write a grocery list without winning a major award. Despite that, it's true that his name doesn't trip off the tongue of the average teen reader, at least here in Canada. He's not an easy author to get into. His writing is challenging and his themes are serious. His humour, when it's there, is cerebral and ironic. His stories are often told in flashback by adult narrators, who range from mildly world-weary to downright bitter. His endings tend towards ambiguity. There is a constant undercurrent of debate in the teen lit world about what, exactly, makes his work teen rather than adult fiction. My opinion? Life: An Exploded Diagram is teen fiction because Peet published it that way, and if he and Candlewick believe that there are enough young readers around who find a detailed exploration of the relationships between 20th-century social history, military history, and personal narrative compelling, well, more power to them. I'm sure not going to stand in the way of their optimism.

That said, however, I do think Peet's books are for older teens with lots of reading experience behind them. For one thing, the way he hangs a story together can be a little complicated. The protagonist of Life is Clem Ackroyd, who is born in chapter one as World War II draws to a close:

"Ruth Ackroyd was in the garden checking the rhubarb when the RAF Spitfire accidentally shot her chimney pot to bits. The shock of it brought the baby on three weeks early.

'I was expectun,' she'd often say, over the years. 'But I wunt expectun that.'"

Fair enough. But no sooner have we met baby Clem, who had "grown in Ruth, struggling and undiscussed" while his father was at war, than we are whisked back in time to become better acquainted with the life of his dour grandmother Win, and later, his mother Ruth and her soldier husband. They are not particularly happy people, and they live in an unsettled time. Win grows up in rural Norfolk, in a time where horses pulled plows and landowners collected rent once a year on Lady Day and celebrated the harvest with a feast for the workers. As pastoral as it sounds, it's not idyllic; Win and her family must cope with illness and poverty and their many consequences. As the years go by Peet gives us a long-term view of 20th century modernization: the farm is slowly mechanized, the family moves into a new suburban home, and the landscape of the country changes. Win's daughter Ruth marries and has a son, and that son, Clem, wins a scholarship to a fancy school and gets an education far above his station. And all of that is merely context for the heart of the story, which is Clem's intense adolescent experience of falling in love with the landowner's daughter Frankie Mortimer. After two dreary generations of emotional repression and marital disappointment, it feels like spring after a long, cold winter.

One of the things I liked best about Life: An Exploded Diagram was how Peet provided a political backdrop to his love story. As Clem and Frankie are courting, Kennedy and Khruschev are becoming embroiled in what would later be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. The way that Peet plays these two stories off of each other sharpens them both, the Missile Crisis reminding us of the fragility of life just as Clem and Frankie's love story is affirming the value of it. I'm a person whose mind normally shuts down when confronted with political history, and even when I try desperately stay tuned in all I tend to hear is "blah blah blah blah blah", so it's a tribute to Peet's excellent writing that I not only stayed wide awake during these chapters but totally understood what was going on.

Here's the publisher's book trailer:

(Karen Silverman, Heavy Medal blog, School Library Journal website)

Mal Peet can't write a grocery list without winning a major award. Despite that, it's true that his name doesn't trip off the tongue of the average teen reader, at least here in Canada. He's not an easy author to get into. His writing is challenging and his themes are serious. His humour, when it's there, is cerebral and ironic. His stories are often told in flashback by adult narrators, who range from mildly world-weary to downright bitter. His endings tend towards ambiguity. There is a constant undercurrent of debate in the teen lit world about what, exactly, makes his work teen rather than adult fiction. My opinion? Life: An Exploded Diagram is teen fiction because Peet published it that way, and if he and Candlewick believe that there are enough young readers around who find a detailed exploration of the relationships between 20th-century social history, military history, and personal narrative compelling, well, more power to them. I'm sure not going to stand in the way of their optimism.

That said, however, I do think Peet's books are for older teens with lots of reading experience behind them. For one thing, the way he hangs a story together can be a little complicated. The protagonist of Life is Clem Ackroyd, who is born in chapter one as World War II draws to a close:

"Ruth Ackroyd was in the garden checking the rhubarb when the RAF Spitfire accidentally shot her chimney pot to bits. The shock of it brought the baby on three weeks early.

'I was expectun,' she'd often say, over the years. 'But I wunt expectun that.'"

Fair enough. But no sooner have we met baby Clem, who had "grown in Ruth, struggling and undiscussed" while his father was at war, than we are whisked back in time to become better acquainted with the life of his dour grandmother Win, and later, his mother Ruth and her soldier husband. They are not particularly happy people, and they live in an unsettled time. Win grows up in rural Norfolk, in a time where horses pulled plows and landowners collected rent once a year on Lady Day and celebrated the harvest with a feast for the workers. As pastoral as it sounds, it's not idyllic; Win and her family must cope with illness and poverty and their many consequences. As the years go by Peet gives us a long-term view of 20th century modernization: the farm is slowly mechanized, the family moves into a new suburban home, and the landscape of the country changes. Win's daughter Ruth marries and has a son, and that son, Clem, wins a scholarship to a fancy school and gets an education far above his station. And all of that is merely context for the heart of the story, which is Clem's intense adolescent experience of falling in love with the landowner's daughter Frankie Mortimer. After two dreary generations of emotional repression and marital disappointment, it feels like spring after a long, cold winter.

One of the things I liked best about Life: An Exploded Diagram was how Peet provided a political backdrop to his love story. As Clem and Frankie are courting, Kennedy and Khruschev are becoming embroiled in what would later be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. The way that Peet plays these two stories off of each other sharpens them both, the Missile Crisis reminding us of the fragility of life just as Clem and Frankie's love story is affirming the value of it. I'm a person whose mind normally shuts down when confronted with political history, and even when I try desperately stay tuned in all I tend to hear is "blah blah blah blah blah", so it's a tribute to Peet's excellent writing that I not only stayed wide awake during these chapters but totally understood what was going on.

Here's the publisher's book trailer:

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos

"He turned and walked out of the room to prepare for his trip. I stood up and closed the door and sat on the edge of the bed feeling very different from myself. Maybe I felt like a city before it was invaded. Or a ship before it sank. Or happiness before it turned into sadness. I couldn't say exactly. But something was about to change in me."

I've never had the privilege of seeing Jack Gantos speak in person, but a colleague of mine has, and when I asked her about the experience the first thing she said was "He's not an ordinary person." Gantos, the author of the Rotten Ralph books for young readers, the extraordinary prison memoir Hole In My Life, and the Joey Pigza chapter book series about a boy going through school and life with ADHD, has built a distinguished career writing about people and situations that are at least a little off-beat. I have no problem believing that he's not an ordinary person. What I didn't realize up until now was how unusual his life circumstances have been, as well. For instance, remember his teen book Love Curse of the Rumbaughs, about the sixty-something siblings whose love for their mother was so obsessive that upon her death they taxidermied her body and kept it in their home? I thought Gantos had been watching Psycho a few too many times, but it turns out that that's a true story. The Rumbaughs are maternal relatives of Gantos, and they actually did taxidermy their dead Mom. No wonder his tone has at times been referred to as "gothic".

But there's so much more depth to Gantos as a writer than his quirky appreciation for the the outliers of society. He's a man of intelligence and intellectual passion, and of long-practiced observation, and of humour. His strengths are all on display in his latest middle-school book, Dead End In Norvelt, which is largely based on events in his own childhood.

Jack grew up in the historic town of Norvelt, Pennsylvania, a model community created during the Depression by Eleanor Roosevelt, whose idealistic presence in this book looms large. Roosevelt (after whom the town is named) planned Novelt and similar communities to be self-sufficient, running on a barter system rather than cash, with large lots for people to grow food for their families. His mother makes sure she raises enough corn each year to share with the town elderly. But by the time Jack is born, the principles the community was founded on have begun to erode.

"'Why'd you offer him fruit and pickles?' I asked, and looked up at her face which didn't look so bright and cheery. 'Doctors cost money.'

'You shouldn't be embarrassed,' Mom said, knowing that I was. 'Money can mean a lot of different things. When I was a kid we traded for everything. Nobody had any cash. If you wanted your house built, you helped someone build theirs, and then they would turn around and help you build yours. It was the same with everything. I'd give you eggs and you'd pay me in milk.'

'I don't think it works that way now,' I remarked. 'If he fixed my nose I don't think he'd want me to do brain surgery on him.'"

In the spirit of neighbour helping neighbour, Jack's mother farms him out one summer to assist Miss Volker, the elderly town nurse, who is now too arthritic to write obituaries (which she sees as a "final medical report" for the dying original town inhabitants). Miss Volker's obituaries are amazingly detailed and personal, and deliberately stuffed with both local and world history. Gradually, as Jack and Miss Volker share a number of unlikely and sometimes hilarious adventures, her passion for history and its importance starts making a lot of sense to Jack, as well as to us.

Here's the snappy publisher-produced book trailer:

And here, courtesy of the Library of Congress, is a rather long but informative talk by Gantos about his career in general and Dead End In Norvelt in particular.

I'll leave you with an endorsement by Jon Scieszka, uber-famous writer, founder of the Guys Read foundation, and the U.S. National Ambassador for Young People's Literature:

"Nobody can tell a story like Jack Gantos can. And this is a story like no other. It's funny. It's thoughtful. It's history. It's weird. But you don't need me to attempt to describe it. Get in there and start reading Gantos."

I've never had the privilege of seeing Jack Gantos speak in person, but a colleague of mine has, and when I asked her about the experience the first thing she said was "He's not an ordinary person." Gantos, the author of the Rotten Ralph books for young readers, the extraordinary prison memoir Hole In My Life, and the Joey Pigza chapter book series about a boy going through school and life with ADHD, has built a distinguished career writing about people and situations that are at least a little off-beat. I have no problem believing that he's not an ordinary person. What I didn't realize up until now was how unusual his life circumstances have been, as well. For instance, remember his teen book Love Curse of the Rumbaughs, about the sixty-something siblings whose love for their mother was so obsessive that upon her death they taxidermied her body and kept it in their home? I thought Gantos had been watching Psycho a few too many times, but it turns out that that's a true story. The Rumbaughs are maternal relatives of Gantos, and they actually did taxidermy their dead Mom. No wonder his tone has at times been referred to as "gothic".

But there's so much more depth to Gantos as a writer than his quirky appreciation for the the outliers of society. He's a man of intelligence and intellectual passion, and of long-practiced observation, and of humour. His strengths are all on display in his latest middle-school book, Dead End In Norvelt, which is largely based on events in his own childhood.

Jack grew up in the historic town of Norvelt, Pennsylvania, a model community created during the Depression by Eleanor Roosevelt, whose idealistic presence in this book looms large. Roosevelt (after whom the town is named) planned Novelt and similar communities to be self-sufficient, running on a barter system rather than cash, with large lots for people to grow food for their families. His mother makes sure she raises enough corn each year to share with the town elderly. But by the time Jack is born, the principles the community was founded on have begun to erode.

"'Why'd you offer him fruit and pickles?' I asked, and looked up at her face which didn't look so bright and cheery. 'Doctors cost money.'

'You shouldn't be embarrassed,' Mom said, knowing that I was. 'Money can mean a lot of different things. When I was a kid we traded for everything. Nobody had any cash. If you wanted your house built, you helped someone build theirs, and then they would turn around and help you build yours. It was the same with everything. I'd give you eggs and you'd pay me in milk.'

'I don't think it works that way now,' I remarked. 'If he fixed my nose I don't think he'd want me to do brain surgery on him.'"

In the spirit of neighbour helping neighbour, Jack's mother farms him out one summer to assist Miss Volker, the elderly town nurse, who is now too arthritic to write obituaries (which she sees as a "final medical report" for the dying original town inhabitants). Miss Volker's obituaries are amazingly detailed and personal, and deliberately stuffed with both local and world history. Gradually, as Jack and Miss Volker share a number of unlikely and sometimes hilarious adventures, her passion for history and its importance starts making a lot of sense to Jack, as well as to us.

Here's the snappy publisher-produced book trailer:

And here, courtesy of the Library of Congress, is a rather long but informative talk by Gantos about his career in general and Dead End In Norvelt in particular.

I'll leave you with an endorsement by Jon Scieszka, uber-famous writer, founder of the Guys Read foundation, and the U.S. National Ambassador for Young People's Literature:

"Nobody can tell a story like Jack Gantos can. And this is a story like no other. It's funny. It's thoughtful. It's history. It's weird. But you don't need me to attempt to describe it. Get in there and start reading Gantos."

Monday, October 17, 2011

Slog's Dad by David Almond, Illustrated by Dave McKean

"'They can hack your body into a hundred bits,' he'd say, 'But they cannot hack your soul.'"

It's difficult to imagine the audience for this moody, unusual story. In a way it's a typical David Almond book--mysterious, earthy, otherworldly, a little unsettling, a little wonderful. Almond's body of work is mostly composed of chapter books for the 8-12 age group, and although this story is much shorter and heavily illustrated I couldn't imagine giving it to a child younger than eight. In fact, I think Dave McKean's illustrations ramp up the creepy/sad qualities to the tale (although those are certainly not the only moods they evoke). I would say that with Slog's Dad, Almond and McKean have together created a highly original work of art for children who are mature enough to handle some emotional ambiguity.

For those of you who don't know David Almond, he's an internationally recognized British writer who has won the Whitbread Award twice, the Carnegie Medal once and has been awarded the very prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal by IBBY International for his lifetime achievement. His first novel, Skellig, has been adapted into a radio play by the BBC and into an Opera which was reviewed as "mysterious, eerie and enthralling" by the Guardian. For those of you who are not familiar with Dave McKean, well, what can I say? Go read The Graveyard Book, or Coraline, or The Wolves in the Walls. He's an artist/photographer/illustrator whose work tends to be matched with writing that has a certain fantastical quality. The pairing of these two here is very powerful. McKean digs into the rich emotion of Almond's story and allows us to slow down and linger over the complexity of it.

Slog's Dad is told from the point of view of Davie, whose friend Slog's father has just died of a slow, devouring illness which robbed him of his legs before it robbed him of life. Slog's Dad promised on his deathbed that he would return for a visit in the spring. Slog believes his father's promise implicitly, but Davie is more practical. For Davie, dead is dead. So when Slog sees a dirty, apparently homeless man sitting on a bench in the springtime, he believes it is his father come for the promised visit. Davie, and we as readers, resist seeing the miracle.

"Slog looked that happy as I walked towards them. He was leaning on the bloke and the bloke was leaning back on the bench grinning at the sky. Slog made a fist and face of joy when he saw me.

'It's Dad, Davie!' he said. 'See? I told you.'

I stood in front of them.

'You remember Davie, Dad,' said Slog.

The bloke looked at me. He looked nothing like the Joe Mickley I used to know. His face was filthy but it was smooth and his eyes were shining bright.

....'He looks a bit different,' said Slog. 'But that's just cos he's been...'

'Transfigured,' said the bloke.

'Aye,' said Slog. 'Transfigured. Can I show him your legs, Dad?'

Slog's Dad is about grief, hope, and, possibly, resurrection. It's also about love and how tenderly it can be bestowed upon even the most humble of us.

"Once I stood with Mam at the window and watched Mrs. Mickley stroke her husband's head and gently kiss his cheek.

'She's telling him he's going to get better,' said Mam.

We saw the smile growing on Joe Mickley's face.

'That's love,' said Mam. 'True love.'"

But Almond's vision of love and resurrection isn't typical. Cold looks, glittering eyes, twisted faces and the stink of garbage mingle uneasily with the image of a man who's gone to heaven. Almond makes it difficult for the reader to make the leap of identification from Davie's closed, doubting heart to Slog's open, accepting one. Even once we believe, we are left questioning: what manner of miracle is this? I love the ambiguity and full emotion of this story. I love how this short book made me think and feel and re-read. There's a lot of depth in this murky, marvellous tale.

It's difficult to imagine the audience for this moody, unusual story. In a way it's a typical David Almond book--mysterious, earthy, otherworldly, a little unsettling, a little wonderful. Almond's body of work is mostly composed of chapter books for the 8-12 age group, and although this story is much shorter and heavily illustrated I couldn't imagine giving it to a child younger than eight. In fact, I think Dave McKean's illustrations ramp up the creepy/sad qualities to the tale (although those are certainly not the only moods they evoke). I would say that with Slog's Dad, Almond and McKean have together created a highly original work of art for children who are mature enough to handle some emotional ambiguity.

For those of you who don't know David Almond, he's an internationally recognized British writer who has won the Whitbread Award twice, the Carnegie Medal once and has been awarded the very prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal by IBBY International for his lifetime achievement. His first novel, Skellig, has been adapted into a radio play by the BBC and into an Opera which was reviewed as "mysterious, eerie and enthralling" by the Guardian. For those of you who are not familiar with Dave McKean, well, what can I say? Go read The Graveyard Book, or Coraline, or The Wolves in the Walls. He's an artist/photographer/illustrator whose work tends to be matched with writing that has a certain fantastical quality. The pairing of these two here is very powerful. McKean digs into the rich emotion of Almond's story and allows us to slow down and linger over the complexity of it.

Slog's Dad is told from the point of view of Davie, whose friend Slog's father has just died of a slow, devouring illness which robbed him of his legs before it robbed him of life. Slog's Dad promised on his deathbed that he would return for a visit in the spring. Slog believes his father's promise implicitly, but Davie is more practical. For Davie, dead is dead. So when Slog sees a dirty, apparently homeless man sitting on a bench in the springtime, he believes it is his father come for the promised visit. Davie, and we as readers, resist seeing the miracle.

"Slog looked that happy as I walked towards them. He was leaning on the bloke and the bloke was leaning back on the bench grinning at the sky. Slog made a fist and face of joy when he saw me.

'It's Dad, Davie!' he said. 'See? I told you.'

I stood in front of them.

'You remember Davie, Dad,' said Slog.

The bloke looked at me. He looked nothing like the Joe Mickley I used to know. His face was filthy but it was smooth and his eyes were shining bright.

....'He looks a bit different,' said Slog. 'But that's just cos he's been...'

'Transfigured,' said the bloke.

'Aye,' said Slog. 'Transfigured. Can I show him your legs, Dad?'

Slog's Dad is about grief, hope, and, possibly, resurrection. It's also about love and how tenderly it can be bestowed upon even the most humble of us.

"Once I stood with Mam at the window and watched Mrs. Mickley stroke her husband's head and gently kiss his cheek.

'She's telling him he's going to get better,' said Mam.

We saw the smile growing on Joe Mickley's face.

'That's love,' said Mam. 'True love.'"

But Almond's vision of love and resurrection isn't typical. Cold looks, glittering eyes, twisted faces and the stink of garbage mingle uneasily with the image of a man who's gone to heaven. Almond makes it difficult for the reader to make the leap of identification from Davie's closed, doubting heart to Slog's open, accepting one. Even once we believe, we are left questioning: what manner of miracle is this? I love the ambiguity and full emotion of this story. I love how this short book made me think and feel and re-read. There's a lot of depth in this murky, marvellous tale.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Bronxwood by Coe Booth

" He get a little smile on his face, like he laughing at me or something. 'I'm saying, if you don't like it at Cal place no more, you got a room right here. It's all set up for you. You could be laying in that bed tonight. But you ain't moving back in here 'less you ask me if you could. That way, both of us is gonna know the reason you back living with me is 'cause you wasn't man enough to make it on your own.'

I don't get this guy. He losing it for real.

'There's only gonna be one man in this house, Ty. And that man ain't you.'"

Boy, would I ever hate to be Tyrell. Things were bad enough when his family was living in a shelter, his Dad was in jail and his immature, do-nothing Mom was pressuring him to be the "man" of the family (in other words, steal or sell drugs to support her and his younger brother Troy). Talk about a role reversal--aren't mothers supposed to want to keep their kids out of trouble? In Bronxwood, Coe Booth returns to the characters she brought to such vivid life in her debut novel, but adds a twist--Tyrell's brother is in foster care, Tyrell himself is sharing a small apartment with his friend Cal, and his father is being released from jail and is returning to take charge of his dislocated family. The thing is, Tyrell has grown up a lot in the past year, and his father doesn't want to know about it. He wants things back to the way they were before, and Tyrell no longer fits into his family's life.

Coe Booth excels at so many things, but I think she conveys two things really well in this book. One is the sense of pressure that Tyrell feels, the way everyone expects something of him that he's not sure he wants to give. This is a kid without a lot of great options, and he knows it. His friends are drug dealers, one girl he's eyeing wants him to spend money on her that he doesn't have, and the girl he cares about even more is being groomed by a sexual predator. He's good at being a DJ but he can't afford his own equipment. He loves his brother but the foster mother in charge doesn't want him visiting. If Tyrell feels that no one has his back, it's probably because no one does. How can he become the man he wants to be with so much working against him?

I've read lots of books which put young people into dilemmas like this, only to bring in a responsible adult at the end to save the day. But not Booth. She keeps it real. No one's swooping in to help.

Coe Booth's second triumph here is in showing Tyrell finally facing his father as an adult. I think the primary relationship in Bronxwood is between Tyrell and his father, and their relationship is pretty complex. Tyrell's Dad is very much a my-way-or-the-highway kind of guy, and if he feels disrespected, he doesn't hesitate to get violent. Tyrell wants to confront his father with the consequences of his jail time, and he's frustrated by how unrepentant his father is. What Tyrell wants from his father, he's never going to get. At least Tyrell has reached the point where he can begin to separate himself from his father's bad choices. Although Tyrell isn't out of the woods yet, I think that's a sign of hope.

I don't get this guy. He losing it for real.

'There's only gonna be one man in this house, Ty. And that man ain't you.'"

Boy, would I ever hate to be Tyrell. Things were bad enough when his family was living in a shelter, his Dad was in jail and his immature, do-nothing Mom was pressuring him to be the "man" of the family (in other words, steal or sell drugs to support her and his younger brother Troy). Talk about a role reversal--aren't mothers supposed to want to keep their kids out of trouble? In Bronxwood, Coe Booth returns to the characters she brought to such vivid life in her debut novel, but adds a twist--Tyrell's brother is in foster care, Tyrell himself is sharing a small apartment with his friend Cal, and his father is being released from jail and is returning to take charge of his dislocated family. The thing is, Tyrell has grown up a lot in the past year, and his father doesn't want to know about it. He wants things back to the way they were before, and Tyrell no longer fits into his family's life.

Coe Booth excels at so many things, but I think she conveys two things really well in this book. One is the sense of pressure that Tyrell feels, the way everyone expects something of him that he's not sure he wants to give. This is a kid without a lot of great options, and he knows it. His friends are drug dealers, one girl he's eyeing wants him to spend money on her that he doesn't have, and the girl he cares about even more is being groomed by a sexual predator. He's good at being a DJ but he can't afford his own equipment. He loves his brother but the foster mother in charge doesn't want him visiting. If Tyrell feels that no one has his back, it's probably because no one does. How can he become the man he wants to be with so much working against him?

I've read lots of books which put young people into dilemmas like this, only to bring in a responsible adult at the end to save the day. But not Booth. She keeps it real. No one's swooping in to help.

Coe Booth's second triumph here is in showing Tyrell finally facing his father as an adult. I think the primary relationship in Bronxwood is between Tyrell and his father, and their relationship is pretty complex. Tyrell's Dad is very much a my-way-or-the-highway kind of guy, and if he feels disrespected, he doesn't hesitate to get violent. Tyrell wants to confront his father with the consequences of his jail time, and he's frustrated by how unrepentant his father is. What Tyrell wants from his father, he's never going to get. At least Tyrell has reached the point where he can begin to separate himself from his father's bad choices. Although Tyrell isn't out of the woods yet, I think that's a sign of hope.

Read You Should: The Strange Case of Origami Yoda by Tom Angleberger

"The big question: Is Origami Yoda real?

Well, of course he's real. I mean, he's a real finger puppet made out of a real piece of paper.

But I mean: Is he REAL? Does he really know things? Can he see the future? Does he use the Force?

Or is he just a hoax that fooled a whole bunch of us at McQuarrie Middle School?"

I'm kind of bummed that I wasn't the one who thought of writing a story about a Yoda finger puppet who dispenses sage advice from the hand of a grade 6 boy. With a genius premise like that, the book would practically write itself! And I mean, it's not like I don't have lots of practice in Yoda-speak, living with an eight-year-old Clone Wars expert like I do. (He even has a Yoda t-shirt that says "Read you must!" No kidding.)

If you like the Wimpy Kid funny-chapter-book-with-sketches format, you'll like Origami Yoda too. I think the reading level is slightly lower than the Wimpy Kid books, actually, but it's just as visually entertaining. The main character is Tommy, who creates a casebook around whether Origami Yoda's advice is accurate or misleading so he can decide whether or not to ask Sara to dance at the school Fun Night like Origami Yoda told him to. Harvey is the skeptic who Does Not Believe and scribbles his Unbeliever comments all over the casebook. Dwight is the creator and voice of Origami Yoda. His friends don't think much of his intellect, which is why they kind of think Origami Yoda might be for real. How could Dwight possibly come up with advice that actually works?

The sequel to Origami Yoda has just come out and it's called...wait for it...Darth Paper Strikes Back. I've just put it in Ewan's and my to-read pile. Origami Yoda comes with instructions on how to make your very own Yoda finger puppet. I am totally psyched!

And, just for fun, here's a hilarious commercial starring Darth Vader and "The Force".

May the Force be with you, friends!

Well, of course he's real. I mean, he's a real finger puppet made out of a real piece of paper.

But I mean: Is he REAL? Does he really know things? Can he see the future? Does he use the Force?

Or is he just a hoax that fooled a whole bunch of us at McQuarrie Middle School?"

I'm kind of bummed that I wasn't the one who thought of writing a story about a Yoda finger puppet who dispenses sage advice from the hand of a grade 6 boy. With a genius premise like that, the book would practically write itself! And I mean, it's not like I don't have lots of practice in Yoda-speak, living with an eight-year-old Clone Wars expert like I do. (He even has a Yoda t-shirt that says "Read you must!" No kidding.)

If you like the Wimpy Kid funny-chapter-book-with-sketches format, you'll like Origami Yoda too. I think the reading level is slightly lower than the Wimpy Kid books, actually, but it's just as visually entertaining. The main character is Tommy, who creates a casebook around whether Origami Yoda's advice is accurate or misleading so he can decide whether or not to ask Sara to dance at the school Fun Night like Origami Yoda told him to. Harvey is the skeptic who Does Not Believe and scribbles his Unbeliever comments all over the casebook. Dwight is the creator and voice of Origami Yoda. His friends don't think much of his intellect, which is why they kind of think Origami Yoda might be for real. How could Dwight possibly come up with advice that actually works?

The sequel to Origami Yoda has just come out and it's called...wait for it...Darth Paper Strikes Back. I've just put it in Ewan's and my to-read pile. Origami Yoda comes with instructions on how to make your very own Yoda finger puppet. I am totally psyched!

And, just for fun, here's a hilarious commercial starring Darth Vader and "The Force".

May the Force be with you, friends!

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Now Is The Time For Running by Michael Williams

"What is worse than the sound of wood against the bones of your brother? I cannot think of anything worse than that."

This book just plain broke my heart. It's a powerful, hard story out of Zimbabwe and South Africa, but for me the location faded away after a while because the characters and events grabbed my attention so forcefully. This is the kind of book I think of when people talk about literature's power to make us understand "the other", because really, what could be more different from my life than the experience of a homeless teen refugee whose one link to "normalcy" is his love of soccer? But anyone who understands not belonging, or the strength of the love you can feel for someone you need to protect, or the way hope and fear can heighten and fuse together for people in desperate conditions will completely get this book.

Now Is The Time For Running is the story of Deo, who must flee his native village in Zimbabwe with his older brother Innocent when soldiers come to town and slaughter everyone in the name of the President.

"I am Commander Jesus. I am one of the president's men. I was once a leader of the Five Brigade. The president has sent me here because he is unhappy with how you voted in the election. Most of you know that this country was won by the barrel of the gun. There are some among you who fought in the war of liberation. I see it in your eyes. You know who you are, and you should be ashamed of your neighbors. You know what sacrifices were made for the freedom we now enjoy. Should we now let it go at the stroke of a pen? Should one just write an X and let the country go just like that? You voted wrongly at the election. You were not thinking straight. That is why the president sent me here."

Deo and Innocent escape the carnage with their lives, and are the only ones in their village to do so. But the soldiers may return, and they must not be found. Where to go? Their mother had a friend in the police force of a nearby city, but even he cannot help them--when they flee to Captain Washington's home, the soldiers are there too. Captain Washington tells them that they must escape to South Africa. Maybe they will be able to find their father there. The journey is insanely dangerous, and when they finally arrive, they find that the safe haven they have been running to is less welcoming than they could ever have imagined.

Sometimes I think it's harder to read certain types of stories as an adult than as a child, for all that children are supposed to be more sensitive. Children are also more comforted by the happy ending. But as an adult, I know how the numbers break down--the number of children in the world who are refugees or survivors of political violence (lots) versus the numbers of teen refugees who are plucked off the streets and chosen to participate in the Street Soccer World Cup (precious few). I'm not saying the ending felt fake, exactly. It just felt a little desperate, like it was worked in because nothing that might more realistically happen is going to repair the damage that has been done to lives we have come to care about. The three young men who provided Williams with background interviews for this book are still homeless and are currently living "on the streets of Cape Town, under highways, and wherever they can find shelter.". Their lives are the reality behind the fiction.

I haven't even mentioned the crux of the story, that Innocent is intellectually challenged and subject to seizures and obsessive-compulsive behavior. He's a prime target for bullying at the best of times, and not exactly easy to smuggle around.

"I once had a brother. His name was Innocent. He was a very special person and he was my best friend."

This is a great book. Read it when you're feeling strong.

This book just plain broke my heart. It's a powerful, hard story out of Zimbabwe and South Africa, but for me the location faded away after a while because the characters and events grabbed my attention so forcefully. This is the kind of book I think of when people talk about literature's power to make us understand "the other", because really, what could be more different from my life than the experience of a homeless teen refugee whose one link to "normalcy" is his love of soccer? But anyone who understands not belonging, or the strength of the love you can feel for someone you need to protect, or the way hope and fear can heighten and fuse together for people in desperate conditions will completely get this book.

Now Is The Time For Running is the story of Deo, who must flee his native village in Zimbabwe with his older brother Innocent when soldiers come to town and slaughter everyone in the name of the President.

"I am Commander Jesus. I am one of the president's men. I was once a leader of the Five Brigade. The president has sent me here because he is unhappy with how you voted in the election. Most of you know that this country was won by the barrel of the gun. There are some among you who fought in the war of liberation. I see it in your eyes. You know who you are, and you should be ashamed of your neighbors. You know what sacrifices were made for the freedom we now enjoy. Should we now let it go at the stroke of a pen? Should one just write an X and let the country go just like that? You voted wrongly at the election. You were not thinking straight. That is why the president sent me here."

Deo and Innocent escape the carnage with their lives, and are the only ones in their village to do so. But the soldiers may return, and they must not be found. Where to go? Their mother had a friend in the police force of a nearby city, but even he cannot help them--when they flee to Captain Washington's home, the soldiers are there too. Captain Washington tells them that they must escape to South Africa. Maybe they will be able to find their father there. The journey is insanely dangerous, and when they finally arrive, they find that the safe haven they have been running to is less welcoming than they could ever have imagined.

Sometimes I think it's harder to read certain types of stories as an adult than as a child, for all that children are supposed to be more sensitive. Children are also more comforted by the happy ending. But as an adult, I know how the numbers break down--the number of children in the world who are refugees or survivors of political violence (lots) versus the numbers of teen refugees who are plucked off the streets and chosen to participate in the Street Soccer World Cup (precious few). I'm not saying the ending felt fake, exactly. It just felt a little desperate, like it was worked in because nothing that might more realistically happen is going to repair the damage that has been done to lives we have come to care about. The three young men who provided Williams with background interviews for this book are still homeless and are currently living "on the streets of Cape Town, under highways, and wherever they can find shelter.". Their lives are the reality behind the fiction.

I haven't even mentioned the crux of the story, that Innocent is intellectually challenged and subject to seizures and obsessive-compulsive behavior. He's a prime target for bullying at the best of times, and not exactly easy to smuggle around.

"I once had a brother. His name was Innocent. He was a very special person and he was my best friend."

This is a great book. Read it when you're feeling strong.

Saturday, October 1, 2011

God as a Teenage Boy: There Is No Dog by Meg Rosoff

"The truth of this could not be denied. Bob had created the world and then simply lost interest. Since his second week of employment, he'd passed the time sleeping and playing with his wangle, while managing to ignore the existence of his creations entirely.

And was this an excuse for him to be rained with curses and loathing from all mankind? Oh no. Because here was the clever bit: Bob had designed the entire race of murderers, martyrs and thugs with a built-in propensity to worship him. You had to admire the kid. Thick as two lemons, but with flashes of brilliance so intense a person could go blind looking at him."

Anthony McGowan's Guardian review of Rosoff's latest novel suggests that "there isn't another young adult novel like There Is No Dog", and goes on to compare Rosoff's writing with Evelyn Waugh, Muriel Spark and Kurt Vonnegut (for "intellectual playfulness"). What There Is No Dog reminded me of was the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series; There Is No Dog is more grounded (it takes place mostly on earth, not on alien spacecraft) and more emotionally nuanced (the Hitchhiker's Guide, as I recall, is pretty much a straight-up parody). But the books share the same kind of goofy absurdist take on a some of mankind's most vexed questions (Hitchhiker contemplates the meaning of life, while Dog takes a good hard look at the world and extrapolates the nature of God).

So, God. He's a teenage boy, name of Bob. He got the job of Creator of Earth because his wacko mother won it for him in a poker game. ("Bob's credentials (non-existent) did not impress. But the general sense of exhaustion and indifference was such that no one could really be bothered to argue.") He's sloppy, lazy, immature, whiny, lacking in compassion or responsibility. He's lustier than the Rolling Stones in heat and prone to falling in and out of love dramatically and dangerously.

'Mr B remembered another girl, another time, with the face of an angel and the sweetest manners, a child's soft mouth and an expression open and trusting as a lamb. She had seen Bob for what he was, and loved him anyway. Mr B removed his spectacles, hoping to erase the vision in his head. That romance had ended with floods, tornadoes, plague, earthquakes and the girl's execution for heresy, a few weeks before her fourteenth birthday. By special order of Pope Urban II.

And, just our luck, this loser has gone and created man in his own image, "which anyone could see was one big fat recipe for disaster."

Earth's only saving grace is that Mr. B, God's administrative assistant, does care about earth and its creatures and tries his damndest to straighten out Bob's messes. (Right now he's dealing with the biblically-proportioned floods caused by Bob's trying to seduce a young girl named Lucy.) But Mr. B is nearing the end of his rope and has applied for a transfer. Who will look after creation now?

Although There Is No Dog sounds like it could be desperately cynical, in the end it isn't. Despite God's blunderings, miracles unexpectedly occur and death is cheated, at least for the moment. People have hope, and it doesn't feel empty. And it may turn out that our slacker of a God can be overthrown....

Nothing is finally resolved in this book, but then again, that's life, isn't it?

And was this an excuse for him to be rained with curses and loathing from all mankind? Oh no. Because here was the clever bit: Bob had designed the entire race of murderers, martyrs and thugs with a built-in propensity to worship him. You had to admire the kid. Thick as two lemons, but with flashes of brilliance so intense a person could go blind looking at him."

Anthony McGowan's Guardian review of Rosoff's latest novel suggests that "there isn't another young adult novel like There Is No Dog", and goes on to compare Rosoff's writing with Evelyn Waugh, Muriel Spark and Kurt Vonnegut (for "intellectual playfulness"). What There Is No Dog reminded me of was the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series; There Is No Dog is more grounded (it takes place mostly on earth, not on alien spacecraft) and more emotionally nuanced (the Hitchhiker's Guide, as I recall, is pretty much a straight-up parody). But the books share the same kind of goofy absurdist take on a some of mankind's most vexed questions (Hitchhiker contemplates the meaning of life, while Dog takes a good hard look at the world and extrapolates the nature of God).

So, God. He's a teenage boy, name of Bob. He got the job of Creator of Earth because his wacko mother won it for him in a poker game. ("Bob's credentials (non-existent) did not impress. But the general sense of exhaustion and indifference was such that no one could really be bothered to argue.") He's sloppy, lazy, immature, whiny, lacking in compassion or responsibility. He's lustier than the Rolling Stones in heat and prone to falling in and out of love dramatically and dangerously.

'Mr B remembered another girl, another time, with the face of an angel and the sweetest manners, a child's soft mouth and an expression open and trusting as a lamb. She had seen Bob for what he was, and loved him anyway. Mr B removed his spectacles, hoping to erase the vision in his head. That romance had ended with floods, tornadoes, plague, earthquakes and the girl's execution for heresy, a few weeks before her fourteenth birthday. By special order of Pope Urban II.

And, just our luck, this loser has gone and created man in his own image, "which anyone could see was one big fat recipe for disaster."

Earth's only saving grace is that Mr. B, God's administrative assistant, does care about earth and its creatures and tries his damndest to straighten out Bob's messes. (Right now he's dealing with the biblically-proportioned floods caused by Bob's trying to seduce a young girl named Lucy.) But Mr. B is nearing the end of his rope and has applied for a transfer. Who will look after creation now?

Although There Is No Dog sounds like it could be desperately cynical, in the end it isn't. Despite God's blunderings, miracles unexpectedly occur and death is cheated, at least for the moment. People have hope, and it doesn't feel empty. And it may turn out that our slacker of a God can be overthrown....

Nothing is finally resolved in this book, but then again, that's life, isn't it?

Monday, September 26, 2011

The Sky Over the Louvre by Jean-Claude Carrier and Bernar Yslaire

I reviewed this gorgeous graphic book over on my work blog. If you're into art or history, go give it a read!

Monday, September 19, 2011

Level Up by Gene Luen Yang, Illustrated by Thien Pham

"To provide that boy with the life he has, I've had to eat much bitterness. He must learn to do the same. How will a video game teach him to eat bitterness?"

"To provide that boy with the life he has, I've had to eat much bitterness. He must learn to do the same. How will a video game teach him to eat bitterness?" Hmmm. Gene Luen Yang. He's one of those writers that for me can go either way. He made his reputation with American Born Chinese, the first and (so far) only graphic novel to win the Michael L. Printz award for excellence in young adult fiction. It was fresh and ingenious, and I liked it a lot. He followed up with The Eternal Smile, which got great reviews but left me cold, and Prime Baby , which I thought was clever and funny but less complex than his first book. In Level Up I think we're seeing him return to his strengths. Level Up is relevant, surprising, engaging, imaginative. Writing about the pressures of parental expectations on young people who live in our pleasure-centric culture, Yang invites readers to think about whether it is our destiny to fulfill our family's hopes and dreams, particularly if they have sacrificed their own for us.

Level Up follows the life of Dennis Ouyang, a high-schooler back in the early days of pac-man. Dennis is enthralled by this new game, and eagerly asks his father for a Nintendo Entertainment System for Christmas (he does this by taping pictures of it to his father's mirror, his newspaper, the fridge, etc.--he and his dad aren't really big on talking together). His parents, to his crushing disappointment, get him a chemistry set instead and his dad leaves notes around the house entitled "How to get into college", "The job market", and "The virtue of work". There, in a nutshell, is the heart of the story.

Dennis works hard and does well in high school to please his parents, but when his father dies just before high school graduation, Dennis immediately goes to an electronics store and gets a game system. On his way home from the funeral. Literally. He becomes a hard-core gamer, flunking out of his $10,000.00-a-year college because he is too distracted to study or attend classes. And then--a miracle!

Angels enter Dennis's life. Four adorable little floating angels who tell him that his destiny is in gastroenterology ("Great shall you be in your profession!", they earnestly proclaim). Four very bossy angels who seem to have come from his father, who bully the dean into re-admitting him to college, who get him to give away all his games and gaming systems, and who move in with him to keep him on the straight and narrow. But the road to gastroenterology is long, hard, and smelly. Does Dennis have what it takes to endure? And even if he can, should he?

What I like about Level Up (apart from the imaginative twists and turns of the story) is the multi-faceted point of view from which Yang explores this dilemna. Many books, movies, and tv shows for teens are all about living your dreams, letting your passions direct your life, and not letting anything get in your way. Yang shows both sides of the equation: how hard it is to work towards something that doesn't inspire you, but also, how practical goals can keep us from frittering away our lives.

Here's a link to an interesting interview with both Yang and illustrator Pham, and here's a link to Yang's website. And finally, here's a video of Yang and Pham talking up their book at San Diego Comic Con, and a link to a comic Yang made explaining the "secret origins" of Level Up.

Labels:

Gene Luen Yang,

Level Up,

Teen graphic books,

Thien Pham

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Happyface by Stephen Emond

"Today is the day the world changed, and that is all I will say because I don't ever want to think of it again."

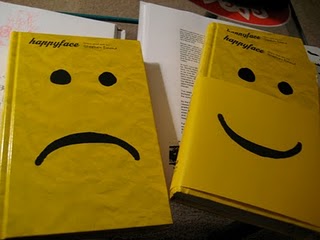

Happyface reminds me a lot of one of my all-time favourite picture books, Michael Rosen's Sad Book. Like the Sad Book, Happyface deals with grief that morphs (as it so easily does) into long-term depression. It also reminds me of Sherman Alexie's The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian in that it is heavily illustrated with the narrator's sketches, and the illustrations do a great deal to enhance the mood of the story. There's a lot going on here visually--starting with the cover. With the book jacket on, we see a happy face, but if we look underneath, the face is sad. (Just like Quentin Blake's brilliant first-page illustration for the Sad Book).

Happyface is about an artistic guy whose family falls apart in a horrible way (how horrible it is, we don't learn until about halfway through the book because Happyface can't talk about it) which leaves him feeling deeply betrayed as well as permanently grief-ridden. Happyface and his mother move to a small apartment in a new neighbourhood where his mother drinks too much and rides a private and painful emotional roller coaster, and he goes to a new school where no one knows him. Happyface decides to reinvent himself, and at first he's pretty successful. He "slaps on a grin", gets his nickname, makes friends with the cool crowd, and starts chasing a girl who's beautiful, reads Allen Ginsberg and seems to like him back. He's fooling everyone.

Of course, eventually everything crumbles around him, because a) people start digging for the truth, and b) he starts going just a little nuts, in the way that happens when you repress such powerful feelings. He turns mean and desperate. We're not even sure we like him anymore.

Emond has chosen to give us the closure of a hopeful ending, although I really felt that this book could have gone either way. Happyface mends some rifts, particularly with his father, and vows that "my problems and failures will not stop me, nor will they dictate who I am". Frankly, the ending wasn't my favourite part. What I found fascinating was how well Emond captured the complications of functioning in a depressed state, because, let's face it, Happyface is right--grief and rage are big social turn-offs for most people, particularly if they last a long time. Sometimes the mask is what saves us.

I also found the illustrations extraordinarily engaging. They're plentiful, sometimes cartoony and sometimes more artistically rendered, and they add a lot of energy and vitality to what could otherwise have been a much more sober story. Here's an interesting article written by Connie Tsu on the Blue Rose Girls blog about the process of editing a book as visual as Happyface. Enjoy!

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

Mirages Don't Have Chicken Breath, Mister: The Trouble With Chickens by Doreen Cronin

"There's an easy way to do a search and a hard way.

The easy way is early in the evening with a cool breeze and a steady partner.

The hard way is high noon with a crazy chicken clucking in your ear and two feather balls riding your tail.

This search was gonna go the hard way."

This easy chapter book lends itself to dramatic reading. It's a send-up of the hard-boiled detective genre; J.J., a retired search-and-rescue dog, is hired by a local chicken to find two missing chicks (he won't work for chicken feed or feathers, but she promises him a cheeseburger). There are lots of good bits to act out, like:

"I never backed down from a staring contest in my life, but her eyes were so tiny and close-set, it was making me cross-eyed."

or:

"I sucked my breath in through my nose as hard as I could. Sugar was dragged right between the two bars and stuck to my nose like a stray sock on a freshly dried towel."

(Sugar is one of the missing chicks. Just picture it. )

Jokes abound, and they're really funny. One of them involves a ransom note which contains the words "behoove", "rendezvous", and "twilight". Our sardonic narrator J.J. observes:

"I've been lowered from a helicopter, strapped to a snowmobile, and flown first-class to France to find a backcountry skier lost in the Alps.

Not once did anyone find it necessary to use the word behoove."

If I want to get a laugh out of my son now, all I have to do is tell him that it behooves him to rendezvous with me at the dinner table.

Like many of the best books for this reading level, lots of illustrations add interest to the text. Here's J.J. enjoying retirement, and J.J. in a peck (bad pun) of trouble.

Just can't trust those chickens.

The easy way is early in the evening with a cool breeze and a steady partner.

The hard way is high noon with a crazy chicken clucking in your ear and two feather balls riding your tail.

This search was gonna go the hard way."

This easy chapter book lends itself to dramatic reading. It's a send-up of the hard-boiled detective genre; J.J., a retired search-and-rescue dog, is hired by a local chicken to find two missing chicks (he won't work for chicken feed or feathers, but she promises him a cheeseburger). There are lots of good bits to act out, like:

"I never backed down from a staring contest in my life, but her eyes were so tiny and close-set, it was making me cross-eyed."

or:

"I sucked my breath in through my nose as hard as I could. Sugar was dragged right between the two bars and stuck to my nose like a stray sock on a freshly dried towel."

(Sugar is one of the missing chicks. Just picture it. )

Jokes abound, and they're really funny. One of them involves a ransom note which contains the words "behoove", "rendezvous", and "twilight". Our sardonic narrator J.J. observes:

"I've been lowered from a helicopter, strapped to a snowmobile, and flown first-class to France to find a backcountry skier lost in the Alps.

Not once did anyone find it necessary to use the word behoove."

If I want to get a laugh out of my son now, all I have to do is tell him that it behooves him to rendezvous with me at the dinner table.

Like many of the best books for this reading level, lots of illustrations add interest to the text. Here's J.J. enjoying retirement, and J.J. in a peck (bad pun) of trouble.

Just can't trust those chickens.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Appetite for Detention by Sloane Tanen

It's back-to-school time. Since my daughter's going into grade eight, I thought the time for reading her picture books was long over, but that was before I stumbled upon Appetite for Detention. Yes, she was skeptical when I offered to read her a bedtime story for old times sake, but the first ridiculous page won her over. It's the contrast between the cute little toy chicks and the angsty-ironic teen dialogue that makes the book such a laugh. Sloane Tanen has made a niche for herself creating these kinds of images with attitude, so if you like the book, check out her website.

Here are a few sample pages:

Here are a few sample pages:

If I were in high school now, I'd tape these to my locker.

Monday, June 13, 2011

Mother Number Zero by Marjolyn Hof

"I think that from the very beginning Bing was always more curious. A Chinese parasol hung from the ceiling in her room, and she owned a pair of Chinese pajamas.

'Why don't you get a Chinese tattoo?' I said.

She pointed at her butt. 'Here?'

'No!' said my mother.

'Yes, right there,' I said. 'Get a dragon.'

'But it has to be a big one,' Bing said. 'A mini dragon would be useless. You'd barely see it.'

'Big and colorful,' I said. 'So it catches your eye. Red, green and blue.'

'And yellow.' Bing said.

My mother looked relieved. 'You're overdoing it. I don't believe you anymore.'

'Overdoing it?' said Bing. 'It's my butt and I can do what I want with it.'

'It's also a little bit mine,' my mother said. 'I wiped it for years.'

'All mothers do that,' Bing said. 'That doesn't mean a thing.' "

Dutch author Marjolyn Hof's Mother Number Zero is a quiet and sensitive story about adoption. Fejzo, called Fay, is part of a Dutch family with two adopted children. His sister An Bing Wa, or Peace-Loving Ice Baby, was adopted from China, while Fejzo's mother was originally from Bosnia. He has a child-like understanding of his past:

"My mother number zero lived in Bosnia and I was in her belly. Mother number zero didn't want a baby. She couldn't take care of me and that was the reason she gave me up. Luckily she didn't give me away to somebody in her own country, because they had a war and far too many problems. She was smart enough to come to the Netherlands, and I traveled along in her belly."

Fay doesn't give too much thought to his adoption until he meets Maud, a newcomer who is very curious about Fay's birth mother. Maud thinks that Fay's birth mother might be a famous artist, since Fay himself is accomplished at drawing birds. She suggests that Fay might be able to find his mother number zero with a bit of detective work, just like on a TV show called Disappeared, where "they search for someone's father or mother and then you can see what happens." The curiosity Maud exhibits eventually stirs something within Fay, and once he begins wondering about mother number zero, he can't seem to stop.

With his parent's assistance, Fay begins to take steps to find his birth mother. Fay doesn't initially understand the difficult feelings this search may spark for both himself and his family, particularly his sister, who was found abandoned and therefore has no means of tracking her birth family. In him, the search evokes many fantasies, some exciting and some frightening.

"And mother number zero? She had gone through a war and given her kid away....Was my mother like some people who could handle it, or like others who couldn't? If she couldn't, then maybe she lived in a park somewhere too. Maybe she drank beer all day long and had a knife to kill ducks. Maybe that was the answer to the question of why she had given me away. She had gone through so much that she had turned into a bum. Maybe she was crazy. Or wounded or crippled. Maybe she didn't have a nose or only one leg or no arms."

Hof, an adoptee herself, enters Fay's inner world with tremendous empathy and understanding. As Fay's thoughts and feelings veer off in so many different directions, we feel safe knowing that he is blessed with parents who are kind and warm, and deeply connected with him. Their support and guidance on his quest helps him prepare for whatever answer will come.

The ending felt right to me, and I found it very honestly and gently handled. This is a story that is simple but never stark. Reading it feels like taking a small pilgrimage and then coming safely back home.

'Why don't you get a Chinese tattoo?' I said.

She pointed at her butt. 'Here?'

'No!' said my mother.

'Yes, right there,' I said. 'Get a dragon.'

'But it has to be a big one,' Bing said. 'A mini dragon would be useless. You'd barely see it.'

'Big and colorful,' I said. 'So it catches your eye. Red, green and blue.'

'And yellow.' Bing said.

My mother looked relieved. 'You're overdoing it. I don't believe you anymore.'

'Overdoing it?' said Bing. 'It's my butt and I can do what I want with it.'

'It's also a little bit mine,' my mother said. 'I wiped it for years.'

'All mothers do that,' Bing said. 'That doesn't mean a thing.' "

Dutch author Marjolyn Hof's Mother Number Zero is a quiet and sensitive story about adoption. Fejzo, called Fay, is part of a Dutch family with two adopted children. His sister An Bing Wa, or Peace-Loving Ice Baby, was adopted from China, while Fejzo's mother was originally from Bosnia. He has a child-like understanding of his past:

"My mother number zero lived in Bosnia and I was in her belly. Mother number zero didn't want a baby. She couldn't take care of me and that was the reason she gave me up. Luckily she didn't give me away to somebody in her own country, because they had a war and far too many problems. She was smart enough to come to the Netherlands, and I traveled along in her belly."

Fay doesn't give too much thought to his adoption until he meets Maud, a newcomer who is very curious about Fay's birth mother. Maud thinks that Fay's birth mother might be a famous artist, since Fay himself is accomplished at drawing birds. She suggests that Fay might be able to find his mother number zero with a bit of detective work, just like on a TV show called Disappeared, where "they search for someone's father or mother and then you can see what happens." The curiosity Maud exhibits eventually stirs something within Fay, and once he begins wondering about mother number zero, he can't seem to stop.

With his parent's assistance, Fay begins to take steps to find his birth mother. Fay doesn't initially understand the difficult feelings this search may spark for both himself and his family, particularly his sister, who was found abandoned and therefore has no means of tracking her birth family. In him, the search evokes many fantasies, some exciting and some frightening.

"And mother number zero? She had gone through a war and given her kid away....Was my mother like some people who could handle it, or like others who couldn't? If she couldn't, then maybe she lived in a park somewhere too. Maybe she drank beer all day long and had a knife to kill ducks. Maybe that was the answer to the question of why she had given me away. She had gone through so much that she had turned into a bum. Maybe she was crazy. Or wounded or crippled. Maybe she didn't have a nose or only one leg or no arms."

Hof, an adoptee herself, enters Fay's inner world with tremendous empathy and understanding. As Fay's thoughts and feelings veer off in so many different directions, we feel safe knowing that he is blessed with parents who are kind and warm, and deeply connected with him. Their support and guidance on his quest helps him prepare for whatever answer will come.

The ending felt right to me, and I found it very honestly and gently handled. This is a story that is simple but never stark. Reading it feels like taking a small pilgrimage and then coming safely back home.

Labels:

adoption,

children's books,

Marjolin Hof,

Mother Number Zero

Saturday, June 4, 2011

Num8ers: The Chaos by Rachel Ward

Although I didn't review British writer Rachel Ward's debut novel Num8ers when it came out last year, I found it intense and fascinating. Num8ers takes place in a contemporary but dystopian England where a girl named Jem has a strange ability: when she looks into people's eyes she sees numbers that represent the date of that person's death. This causes a great deal of trouble for her in terms of the story, as it ultimately leads to her being mistaken for a terrorist . I thought it was an ingenious idea, though. Imagine the questions it raises: is the future preordained? If you warned someone, could you change their fate? Is there a purpose behind this ability? What is the cost to Jem of such knowledge? What makes Jem's situation more intriguing is that she can't see the date of her own death, since of course she can't look herself directly in the eye (mirrors don't work).

Num8ers: The Chaos could also be called Num8ers: The Next Generation. We are now in the year 2026, and Jem has died of cancer. Adam, her son, is living with his grandmother, with whom he often clashes. Adam has inherited his mother's ability to see death in a person's eyes, but in his case the power is intensified: he not only sees the date, he also feels the nature of the death, the emotions and the pain of the process. Because of this disturbing ability and the isolation of being so freakish, he is a troubled, angry teen. He's also scared, because after a flood takes down his mother's old home and his Nan insists they move to London, he can't help but notice that almost everyone he meets has the same death date: January 1st, 2027, and that all of these deaths are traumatic. Something terrible is going to wipe out London soon, and it's up to misfit Adam to do what he can to stop it.

I liked this book even more than Ward's first, in part because having set up the situation already, she can now make it increasingly complex. She adds another point of view, that of Sarah, a girl with big problems and a scary ability of her own. The goverment has grown even more distrustful and controlling, to the point where people are microchipped and can be tracked at all times. The stakes are higher. The ending is unexpected and riveting. But it's not only the tension and suspense that are so compelling; Ward gives her characters a lot of depth and development. This is a book with substance as well as thrills. Ward is planning a third book in the series, titled Num8ers: Infinity, which will focus on Sarah's daughter Mia, so altogether the Num8ers series will span three generations.

Num8ers: The Chaos could also be called Num8ers: The Next Generation. We are now in the year 2026, and Jem has died of cancer. Adam, her son, is living with his grandmother, with whom he often clashes. Adam has inherited his mother's ability to see death in a person's eyes, but in his case the power is intensified: he not only sees the date, he also feels the nature of the death, the emotions and the pain of the process. Because of this disturbing ability and the isolation of being so freakish, he is a troubled, angry teen. He's also scared, because after a flood takes down his mother's old home and his Nan insists they move to London, he can't help but notice that almost everyone he meets has the same death date: January 1st, 2027, and that all of these deaths are traumatic. Something terrible is going to wipe out London soon, and it's up to misfit Adam to do what he can to stop it.

I liked this book even more than Ward's first, in part because having set up the situation already, she can now make it increasingly complex. She adds another point of view, that of Sarah, a girl with big problems and a scary ability of her own. The goverment has grown even more distrustful and controlling, to the point where people are microchipped and can be tracked at all times. The stakes are higher. The ending is unexpected and riveting. But it's not only the tension and suspense that are so compelling; Ward gives her characters a lot of depth and development. This is a book with substance as well as thrills. Ward is planning a third book in the series, titled Num8ers: Infinity, which will focus on Sarah's daughter Mia, so altogether the Num8ers series will span three generations.

Monday, May 30, 2011

Shine by Lauren Myracle

"What I knew was this: Once upon a time, everything changed. Now things had to change again. Someone needed to track down whoever went after Patrick, and that someone was me."

Shine is unequivocally Lauren Myracle's best book to date, and it's a huge leap forward for an author who is already extremely popular, especially among tweens and younger teens. Myracle is largely known for a style that is funny, warm, playful and consistent, a style where happy endings are virtually guaranteed. Shine is not at all like that. Instead, it's psychologically and morally probing. It's suspenseful and deeply absorbing. It's piercing and compassionate. It's nuanced and mature and very obviously written from the heart of a true artist.

Shine takes place in a small Southern town steeped in secrets, tightly-knit loyalties and below-the-surface cruelties. At the centre of the story is Cat, who has retreated into herself since her older brother's friend assaulted her at age 13. As a child, Cat's best friend was Patrick, but as a teenager she has distanced herself from him entirely, even though "losing Patrick was almost the same as losing myself." Now Patrick is in a coma after having been beaten to a bloody pulp at the late-night gas station where he works, and for Cat, this is simply too much to bear. She is consumed with the need to uncover Patrick's attacker, to "look straight into the ugliness and find out who hurt him, and...yell it from the mountaintop." The assault on Patrick is assumed to be a hate crime, since Patrick is openly gay (in fact, he is the only out person in this community, as far as I could see) and he is found with the words "Suck this, faggot" scrawled in blood across his chest and a gas pump duct-taped into his mouth.

Cat's unrelenting quest for the truth disturbs many people and places her in increasing danger. Already intelligent, she becomes almost hyper-observant and soon realizes that even people whom Patrick considered friends may have wished him harm. What I loved most about Shine was the way that Cat kept digging deeper and deeper and really thinking about the people around her, their histories and relationships and what they might or might not be capable of. Cat becomes increasingly adept at seeing beneath the surface of people, noticing the aggression and nastiness hiding underneath the friendship. Through Cat's determination and growing understanding, Myracle shows us the value and the cost of fighting intolerance.

Here's a fan-made video recommended by the author herself:

Shine is unequivocally Lauren Myracle's best book to date, and it's a huge leap forward for an author who is already extremely popular, especially among tweens and younger teens. Myracle is largely known for a style that is funny, warm, playful and consistent, a style where happy endings are virtually guaranteed. Shine is not at all like that. Instead, it's psychologically and morally probing. It's suspenseful and deeply absorbing. It's piercing and compassionate. It's nuanced and mature and very obviously written from the heart of a true artist.

Shine takes place in a small Southern town steeped in secrets, tightly-knit loyalties and below-the-surface cruelties. At the centre of the story is Cat, who has retreated into herself since her older brother's friend assaulted her at age 13. As a child, Cat's best friend was Patrick, but as a teenager she has distanced herself from him entirely, even though "losing Patrick was almost the same as losing myself." Now Patrick is in a coma after having been beaten to a bloody pulp at the late-night gas station where he works, and for Cat, this is simply too much to bear. She is consumed with the need to uncover Patrick's attacker, to "look straight into the ugliness and find out who hurt him, and...yell it from the mountaintop." The assault on Patrick is assumed to be a hate crime, since Patrick is openly gay (in fact, he is the only out person in this community, as far as I could see) and he is found with the words "Suck this, faggot" scrawled in blood across his chest and a gas pump duct-taped into his mouth.

Cat's unrelenting quest for the truth disturbs many people and places her in increasing danger. Already intelligent, she becomes almost hyper-observant and soon realizes that even people whom Patrick considered friends may have wished him harm. What I loved most about Shine was the way that Cat kept digging deeper and deeper and really thinking about the people around her, their histories and relationships and what they might or might not be capable of. Cat becomes increasingly adept at seeing beneath the surface of people, noticing the aggression and nastiness hiding underneath the friendship. Through Cat's determination and growing understanding, Myracle shows us the value and the cost of fighting intolerance.

Here's a fan-made video recommended by the author herself:

Saturday, May 21, 2011

The Good, The Bad and The Barbie: A Doll's History and Her Impact on Us by Tanya Lee Stone

Tanya Lee Stone's The Good, The Bad and The Barbie deserves all the love it's getting. Stone's a great writer and writes the kind of non-fiction that kids will read for fun. This book mines a rich vein since Barbie dolls have been so iconic and yet controversial in our culture. Stone gives us the history of both the doll and of the points of view surrounding the image of womanhood she represents. The two things about The Good, The Bad and The Barbie that I found most interesting were the anecdotes of how people had played with their Barbies as children, and the way various artists and film-makers have used her as creative inspiration. Did you know that there is an annual Altered Barbie Exhibition in San Francisco each year, which "includes music, films, and performance art, as well as paintings and sculpture"? Wild.

Here are some of my favourite quotes and images from the book: